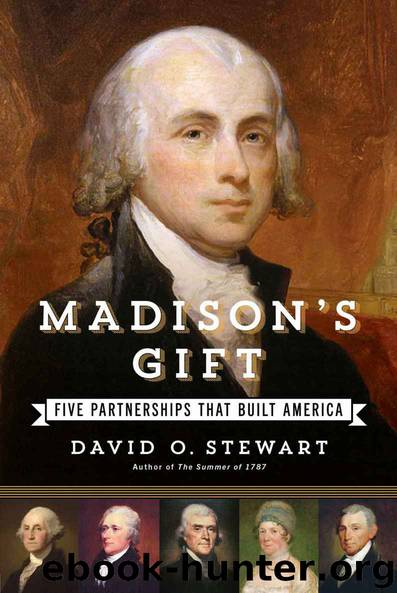

Madison's Gift: Five Partnerships That Built America by David O. Stewart

Author:David O. Stewart [Stewart, David O.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Published: 2015-02-09T23:00:00+00:00

20

THE REPUBLICAN WAY OF WAR

Though he possessed neither military experience nor martial inclinations, Madison was cajoling and hauling the nation into what would become the War of 1812. That contradiction applied to the Republican Party as well. Republicans embraced war but refused to create a military to fight it. They believed in militia, citizen-soldiers who would drop their plows to pick up their muskets, then return to peaceful pursuits when the fighting was over. Moreover, Madison was going to war in 1812, a national election year, which would place the question of war and peace directly before the voters. No other American war has begun in a presidential election year.

No single event triggered the fighting. The greatest British outrage, the Chesapeake affair, had occurred five years earlier. The Erskine Agreement had imploded three years before. Rather than a response to exploding events, the War of 1812 was a howl of wounded pride, fueled by injuries that still rankled years later. As Monroe wrote in 1811, “War, dreadful as the alternative is, could not do us more injury than the present state of things, and it would certainly be more honorable to the nation, and gratifying to the public feelings.” A Virginia Republican called it a metaphysical war, one fought “not for conquest, not for defense, not for sport,” but “for honor, like that of the Greeks against the Trojans.”1

Although Madison’s commitment to war was clear when he called Congress into session early in the fall of 1811, then urged it to place the nation in armor, Republican doctrine dictated that Congress, not the executive, should initiate war. Accordingly, Madison limited his public statements on the subject, though in private he made his view entirely clear. “I believe there will be war,” Dolley wrote to a sister in December 1811, “as M sees no end to our perplexities without it.” According to an account of a February 1812 dinner:

The President, little as he is in bulk, is unquestionably above others in spirit and tone. While they are mere mutes, . . . he on every occasion, and to everybody, talks freely . . . [and] says the time is ripe, and the nation, too, for resistance.

Madison sent Monroe to assure congressmen of his commitment to war and had a key ally in Henry Clay of Kentucky, the thirty-six-year-old Speaker of the House, who also chose war.

Congress, however, continued its fractious ways, unable to seize the lead that Madison urged on it. Jefferson thought it impossible that “a body containing 100 lawyers in it should direct the measures of a war.” When Congress finally adopted a tax increase to pay for war preparations, Madison called it “the strongest proof . . . that they do not mean to flinch from the contest to which the mad conduct of Britain drives them.” Madison applauded congressional moves to prepare an American attack on Canada and began rudimentary planning for such an offensive.2

Frustrated by Congress’s delays, Madison and Monroe tried a daring gambit to jolt the nation into war.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26607)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23090)

Out of India by Michael Foss(16861)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13342)

Small Great Things by Jodi Picoult(7156)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5519)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5104)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4967)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4821)

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4808)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4483)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4367)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(4278)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4208)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4119)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4037)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3973)

Aleister Crowley: The Biography by Tobias Churton(3647)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3472)